As the saying goes, “Don’t blame the person, fix the process.” Weak links in supply chains and service fulfillment have driven demand for better processes globally. When processes cause problems for your customers and your employees, and ultimately your bottom line, business process analysis is the journey to solutions. The fix seems simple: locate the troublesome process, unpack what it looks like today, drill down to the true pain points, and then design a better process.

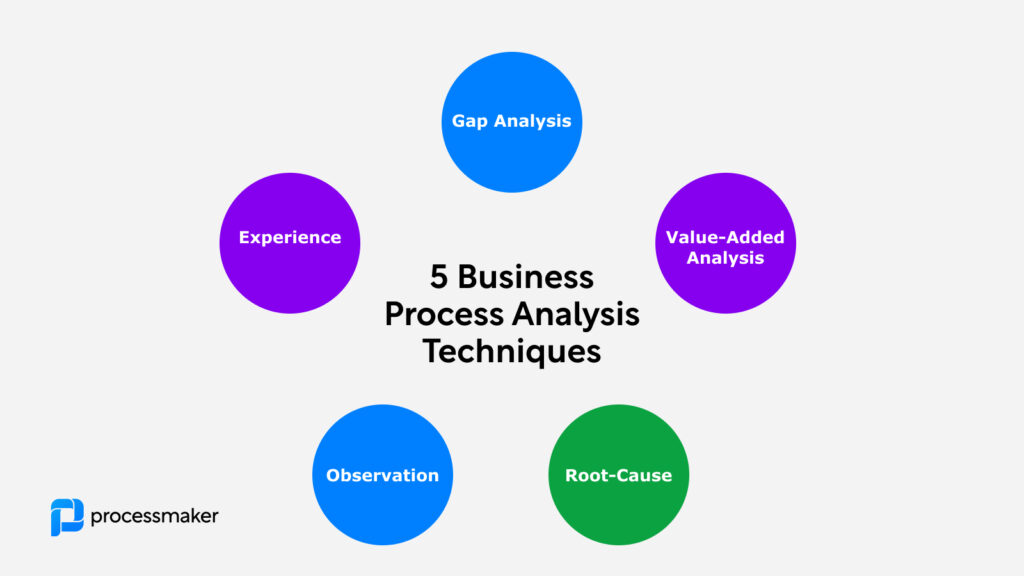

The catch? There are lots of possible ways — or techniques — to get results. And results aren’t all made equal. A misanalyzed process might remain faulty if the true problems go undiscovered. With the five most recurring analysis methods, you can move past decision paralysis and into action. These techniques are:

- Gap analysis

- Value-added analysis

- Root cause analysis

- Observation analysis

- Examining the experience

To patch out the real problems instead of rehashing the same results, you’ll want to use the right techniques for the job. Each has its value, and multiple techniques can be used to extract and solidify your insights. Let’s explore what to be mindful of when choosing from these most-used analysis techniques.

Business process analysis concepts to remember when choosing techniques

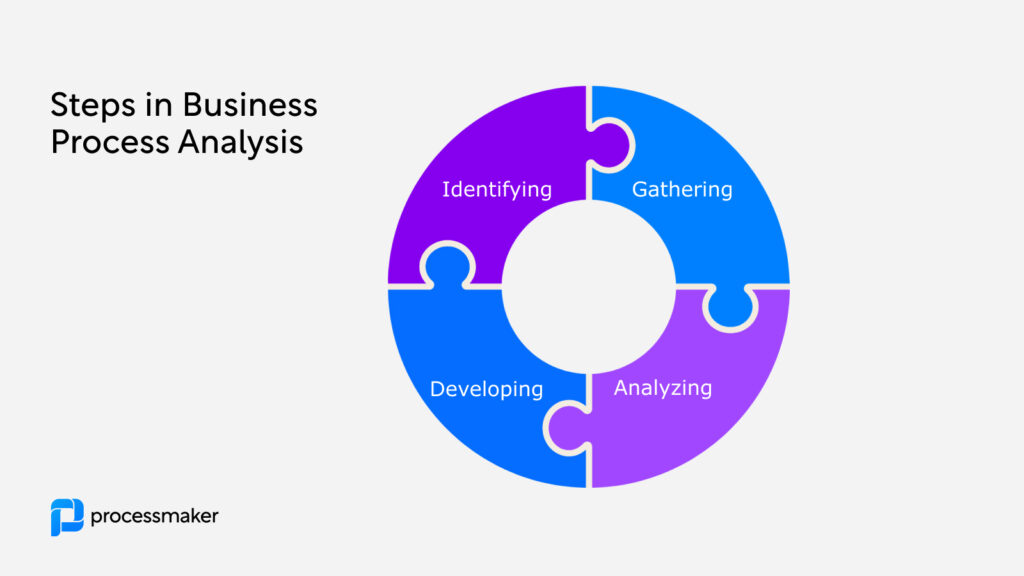

As you choose and put business process analysis techniques to use, you’ll engage in:

- Identifying your process for analysis,

- Gathering intel on the process,

- Analyzing the process “as-is”,

- Developing the improved process “to-be”.

Beginning with your information gathering, you’ll be examining and refining what fuels and shapes the process in question. The four components of any business process are inputs, guides, outputs, and enablers — creating the acronym “IGOE.”

Inputs enter the process to produce results or outputs. Resources known as enablers — tools, systems, human staff, and various assets, as well as the facilities that house them — are used to perform the process. Guides like policies and knowledge from experience decide when, why, and how the process plays out.

To collect and unpack these components, you might discuss the process with stakeholders like frontline employees. Along with interviews and other intel sessions, observation is another information collection and analysis method we’ll be exploring shortly.

1. Gap analysis

Gap analysis finds and reconciles the “gap” between the performance you’re getting, and the performance you want to achieve.

The key concepts at play are as follows:

- Your performance is where your results are now.

- Your potential is where you want to be.

- The gap is created by what’s keeping you from reaching your potential.

- Closing the gap requires an action plan to overcome roadblocks and improve.

Gap analysis is an invaluable way to reconnect with your goals and reorient where your performance is headed.

To evaluate your gap, you’ll look at the relationships between the four business process components.

Starting with input-output relationships may reveal redundancy, wasteful activity, poor task timing, and missing steps.

2. Value-added analysis

Value-added analysis weighs and labels whether any needs are met by each business process step. The technique acts as a broad sorting lens for activities to help your team cut or reduce the non-essentials.

Steps that add “value” must be completed to meet a need of either the customer or the business itself. With this definition in mind, consider what activities in your process fall into these three categories:

- Real value-added (RVA) steps meet an expectation or need of the customer.

- Business value-added (BVA) steps meet an expectation or need of the business.

- Non-value-added (NVA) steps do not meet customer or business needs, or meet needs that can be fulfilled even if the steps are removed.

Assessing value requires digging to the core of why each activity exists. Carefully question all activity within the phases of a process life cycle (i.e. planning, execution, analysis, and adaptation). To do this, you’ll be sorting steps via simple verb-and-noun labels (ex: prioritize support tickets) to establish the purpose and reveal the true value.

3. Root-cause analysis

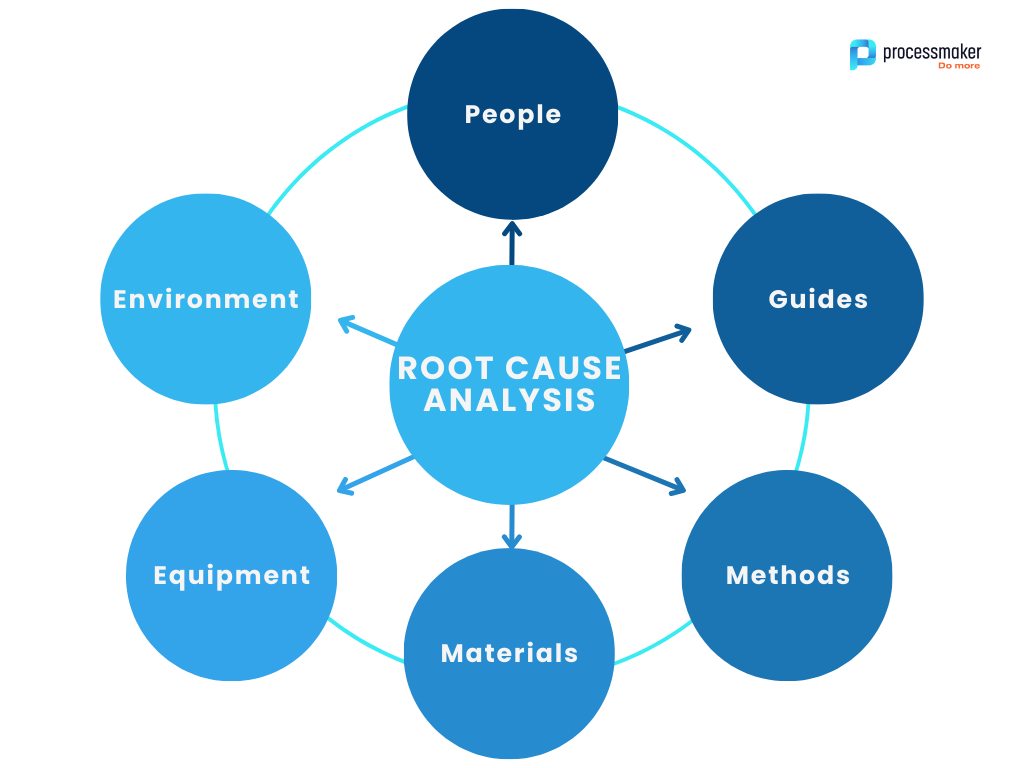

Root cause analysis specializes in finding the core reasons for problems to show each of the possible fixes.

Simple or obvious concerns could hide their own deeper issues that are less visible. Being the ideal technique to drill down to the heart of an issue, root cause analysis is a perfect path for getting beyond assumptions about your problems.

Visualized charts and tables are your primary vehicle for unpacking the root cause relationships. Specifically, the Ishikawa diagram (“cause-and-effect” diagram) is well-suited for clearly showing who and what feeds the undesired outcomes. The subjects investigated may include these specific enablers and guides:

- People or human stakeholders, including staff, supervisors, etc.

- Guides such as references, logs, and schedules.

- Methods like payment processing, request routing, etc.

- Materials include consumables like paper supplies, pens, ink toner, etc.

- Equipment such as physical machines, devices, and other maintainable tools.

- An environment like onsite or offsite spaces that house and support the process.

Between these components lie branching steps that influence the outcome. Even when connective threads are discovered, there may be more to find as analysts gather intel from different perspectives.

4. Observational analysis

As a critical point of information collection, observation reveals overlooked or undervalued steps in a process. It also shows any absent activity, despite being documented or implied as an active part of the process.

Observers can also engage in confirming if employee recall of a process is accurate. Interviews and process mapping sessions can be tainted with an intuition that comes with experience. As novices to the process, analysts may see and question roadblocks that a process vet has come to unconsciously bypass.

An observer may operate under one of two modes:

- Passive observers avoid interacting to keep the process natural and unaffected.

- Active observers jump in with questions and may participate in the process for real-time insights.

Regardless of the method, observation has an important caveat: it introduces your analyst as a foreign presence that may unnaturally shape the process. Unlike any of the other four techniques, observation will shift the analyst from an outsider to a factor in the process itself.

Observers would be wise to plan and clarify their roles with employees. Clear expectations can help keep the process free of distortion. Even in passive observation, being conscious of this influence can allow your team to adjust their conclusions accordingly.

5. Experience examination analysis

Experience examination analysis captures the process knowledge of longtime employees.

Where observation gathers information from a novice perspective, experience examination unpacks lessons learned by expert staff.

Experience-based knowledge is typically undocumented and not often discussed. As a result, the “why” behind these activities may not be recorded through observations, interviews, and other sessions alone.

Targeting veteran employees helps teams find out:

- What fuels high-level productivity in the process?

- What drives faulty activities within the process?

Analysis of this sort can reveal critical connections between root causes and non-value-added (NVA) activities. The impact of these often “invisible” factors — like company culture and unintuitive policies — may be visible only to the experienced staff since they’ve been affected by it for a decade or more. This technique aims to bring that visibility to the wider organization.

If your organization has retained seasoned staff that knows your process thoroughly, experience analysis is pivotal to getting durable results. It also allows teams to retain this exclusive knowledge even after the experts leave the company.

Consider experience analysis whether you’d like to support theories around your other analysis data or if you want to expand your process visibility.

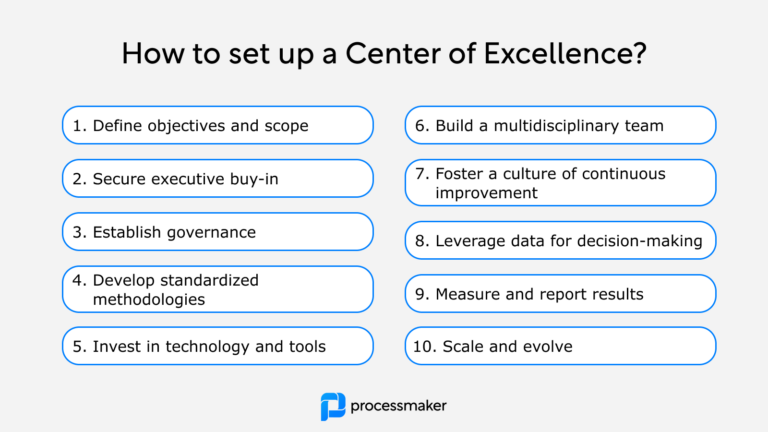

Implementing business process analysis with the right tools

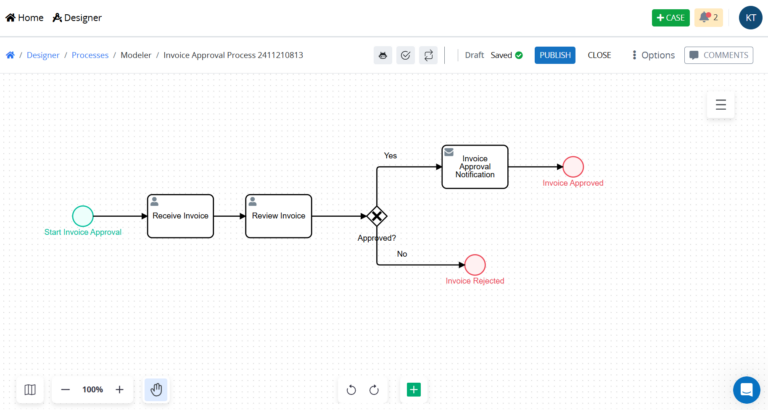

While understanding these analysis techniques is crucial, implementing them effectively requires the right technology stack. Modern business process management (BPM) platforms like ProcessMaker provide the infrastructure needed to:

– Visualize and map complex processes in real-time

– Collect and analyze process performance metrics automatically

– Enable collaboration between stakeholders across departments

– Implement and track process improvements systematically

– Scale successful process changes across the organization

With ProcessMaker’s low-code platform, organizations can transform their analysis insights into actionable improvements quickly and efficiently. The platform’s intuitive interface makes it easier to implement all five analysis techniques while maintaining clear documentation and measurable results.

The path forward with business process analysis

Business process analysis is more than just a methodology—it’s a crucial step toward organizational excellence. When done right, it simplifies your operations by reducing manual effort, minimizing errors, improving consistency, and providing better task management. Most importantly, it creates a foundation for sustainable growth and change.

However, the success of your business process analysis journey largely depends on having the right partner and tools. ProcessMaker’s comprehensive BPM platform is designed to support organizations through every stage of process analysis and improvement. Our solution combines powerful analysis capabilities with intuitive process automation tools, helping organizations not just identify improvements but implement them effectively.